Long Read: Enabling TVWS & protecting incumbents

This article was originally published on the Nominet blog.

Following the Dynamic Spectrum Alliance’s publication of its new Model Rules for TV White Spaces (TVWS), we published a blog giving an overview of the rules and their importance to the global development of TVWS. This second article is a deep-dive into some of the more detailed aspects of the rules, and how they have been crafted to achieve various real-world outcomes.

The purpose of TVWS regulation is to allow and facilitate a technical and commercial ecosystem which provides social and economic benefit to citizens. It should enable the widest possible diversity of technologies and use-cases, while giving strong protection to the incumbent spectrum users (such as TV broadcaster). The DSA Model Rules have two main sections: Technical Rules, which serve to enable TVWS use-cases, and Coexistence Calculations, which protect incumbent users.

Nominet has a production-ready White Space Database (WSDB) applying the DSA Model Rules. Data on the locations of TV transmitters in a country can be imported to produce a fully-functional demonstration WSDB for that country in a matter of hours, along with detailed feasibility studies into the potential benefits of TVWS. The examples below were generated using our tools.

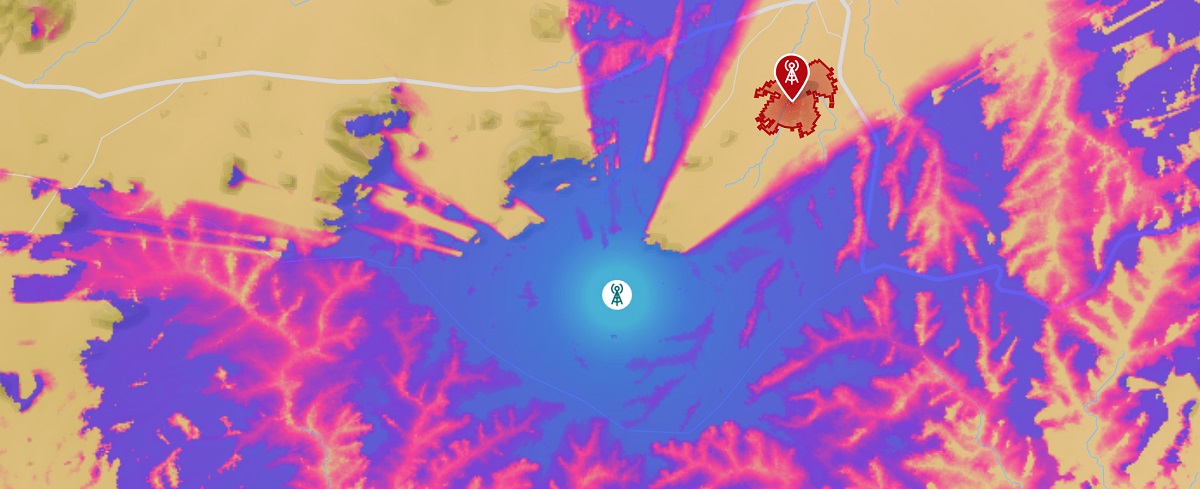

Coverage plot of a TV tower (blue/pink) and a TVWS device fitting into a gap (red).

Coverage plot of a TV tower (blue/pink) and a TVWS device fitting into a gap (red).

Coexistence calculations to protect incumbents

“Given the location and characteristics of a TWVS device, which frequencies can it use at which power levels without causing harmful interference to incumbents such as TV broadcasters?”

This is a simple question, but finding good answers is complicated. The central tenet of TVWS is that answers can be found quickly by an automated service (the WSDB) to provide robust protection to incumbents. It is therefore of paramount importance to devise an accurate and reliable method for answering that question; this takes the form of coexistence calculations.

Ofcom in the UK and FCC in the USA were the pioneers of TVWS regulation and invested considerable effort in their coexistence calculations. A great deal of that work is more generally applicable, but some applies only to the country it was intended for. The DSA Model Rules combine and refine the best aspects of both models to produce coexistence calculations which can be applied anywhere in the world.

Protecting television

To understand how the signals of a TVWS device will interact with incumbent users, we must first understand where the incumbent users are, how strong their reception currently is, and how strong it needs to be.

TV transmitters at the top of hills can reach further, and receivers at the bottom of valleys receive weaker signals. There are many established methods for simulating how TV signals propagate through the atmosphere, over terrain, and through clutter such as trees. These can be used to predict the coverage area of a TV transmitter within which domestic receivers have a good signal. We can predict an interference area around a TVWS device, identifying where its transmissions at similar frequencies to the TV broadcast might cause harmful interference, including safety margins. We can then choose transmit powers for the TVWS device in each frequency to shrink the interference area so it does not overlap with the coverage area. This process is repeated for all TV towers in the vicinity, and so the TVWS device is prevented from causing harmful interference to any domestic users.

While the above describes the broad approach, the FCC and Ofcom models differ in a number of ways.

The FCC model predefines coverage areas around TV transmitters based on how high the transmitter is above the average terrain in each direction. TVWS devices inside or near that area are not permitted to use the similar frequencies as that transmitter. This admirably straightforward approach does, however, admit cases where TVWS devices are over-restricted, particularly where terrain has a large effect.

The Ofcom model simulates TV coverage in considerably more detail. The UK is divided into a grid of 100m pixels. In each pixel which contains households, the signal of each TV transmitter is predicted (taking detailed terrain and clutter into account), and a combined Signal-to-Interference-and-Noise-Ratio (SINR) is found for each signal. A pixel with a suitably high SINR is considered to be in the coverage area of a TV transmission and must be protected from interference. The TVWS device will have its transmit powers restricted to meet the protection requirements of every pixel, with closer pixels causing greater restrictions than further ones.

This high-resolution approach offers an excellent combination of protecting incumbents and making efficient use of spectrum. Ofcom based their coexistence framework on extensive experimental measurements of how TVWS devices interact with domestic television. The pixel-based approach is computationally involved, and uses UK-specific Planning Model software to predict TV coverage. However, the coverage of TVWS devices is modelled as circles with no account of terrain – i.e. a device at the bottom of a cliff will be treated the same as a device at the top – which admits cases of over-restriction.

The DSA Model Rules adopts a coexistence framework based on the Ofcom approach but applicable anywhere. It recommends predicting coverage using the Longley-Rice propagation algorithm, which offers a good trade-off between prediction accuracy and computational expense; other algorithms can be plugged in where appropriate. Where a complete dataset of household locations is not available, every pixel is assumed to contain a household. Terrain is also taken into account when predicting the coverage of a TVWS device, as are further details of its antenna where known (e.g. polarisation, radiation pattern, and directivity).

Further considerations

A number of additional details are required for the model to work equally well in different regions of the world. TV channels are 8MHz wide in Europe, Africa, and some of Asia, but 6MHz wide in the Americas and the rest of Asia. Some countries may enable TVWS in several discrete frequency ranges with uneven gaps in between. Careful treatment is required to harmonise with both the Ofcom and FCC approaches to how TVWS devices (like any radio) leak emissions into adjacent frequencies. Furthermore, default regulation is provided for protecting other incumbents (such as protected zones) and cross-border emissions, which countries can customise for their specific needs.

Enabling TVWS with technical regulation

Enabling country-wide spectrum usage monitoring

The DSA Model Rules, following Ofcom/ETSI, require each TVWS device to report to the WSDB which frequencies and power levels it is currently transmitting at. WSDBs can then provide real-time information to regulators about how TVWS spectrum is being used throughout their country. This enables a spectrum owner to make accurate quantitative analyses of social and economic benefits, and to take immediate mitigating action in the unlikely event of harmful interference.

Enabling transport

Both the Ofcom and FCC models make provision for geolocated mobile/portable devices, but both assume that these devices will not travel very far or very fast. This makes transport-based use cases such as ships and trains impracticable. Both models define the location as a point (with a small uncertainty region) and require the device to request a fresh dynamic licence when the device has moved 100m (US) or 50m (UK) away from this point, so a speed of only 10mph requires a fresh licence every 10-20 seconds.

The DSA model rules solve this problem by allowing the device to report location as a polygon or series of polygons. This ‘flight plan’ approach allows the device’s entire journey to be covered in a single dynamic licence, facilitating the use of TVWS in transport scenarios.

Enabling indoor uses

Radio transmissions taking place inside a building will generally cause less interference to users outside the building due to wall loss. Indoor TVWS devices may therefore, in principle, be awarded higher power limits without further risk of causing harmful interference. The FCC Model makes no account for devices being indoors. The Ofcom model assumes that all mobile devices above 2m are indoors and all other devices are outdoors. The DSA Model Rules instead allow a device to explicitly report whether it is indoors or outdoors, facilitating the use of TVWS in indoor scenarios (e.g. within a large factory building).

Enabling flexible network topologies

A network topology is the manner in which various devices in a network are linked together via wired or wireless physical links.

Under the Ofcom/ETSI model, a master TVWS device must directly contact the WSDB to obtain a dynamic licence for itself and on behalf of its slave devices. Within the bounds of their dynamic licences, TVWS devices may transmit in any topology without causing harmful interference to incumbent users. However, in practice the requirement for direct – i.e. not via another TVWS device – contact between master and WSDB restricts the network to using only the simple ‘star’ topology. A fibre internet connection can then only be shared over only one physical ‘hop’, preventing a TVWS network from extending more than 10-40km from the edge of a not-spot, depending on conditions.

The FCC model allows fixed devices to proxy the WSDB requests of other fixed devices, each of which can maintain its own network of Mode I slave devices. This is an ‘extended star’ topology, enabling ‘multi-hop’ TVWS networks to penetrate deeper into not-spots.

The DSA Model Rules offers greater flexibility by also allowing portable devices in multi-hop or ‘mesh’ networks, which can extend many tens of kilometres into not-spots, and share traffic load via multiple redundant links. Removing regulatory impediments to innovation within the TVWS ecosystem may help TVWS play a major role in connecting people in remote areas and less-connected countries.

Enabling global market development

Ofcom and FCC categorises TVWS devices in similar yet non-compatible ways. For the DSA Model Rules to harmonise with both these existing models, a more generalised categorisation was needed.

Broadly, TVWS devices are categorised according to whether they are fixed or portable/mobile, whether they connect to a WSDB directly or via a proxy, whether they have geolocation capability (GPS or a qualified installer), and whether they can establish their own network of other devices. However, the more relevant question for device manufacturers is “how sophisticated and expensive must the hardware and software be?”. A useful categorisation is then ‘smart’ devices, which know their own geolocation and make their own choices about what spectrum to use, and ‘simple’ client devices, which don’t know geolocation and must be told what spectrum to use.

Under the FCC model, fixed devices are allowed to operate at high power (10W in less-congested areas) but portable devices only at lower power (100mW), regardless of whether they are smart (Mode II in their terminology) or simple (Mode I). This limits the usable radius of portable devices.

Under the Ofcom/ETSI model, all devices are allowed to operate at high power (4W). Simple slave devices use generic power limits (GOPs in their terminology). These are generally far more restrictive than those used by the master device (MOPs) or smart slaves (SOPs). However, smart slaves must first act as simple slaves and use GOPs to handshake with a master, reducing the usable radius of TVWS to only the worst-case GOP power limits.

By combining elements from FCC and Ofcom, the DSA Model Rules allow greater flexibility. All devices – fixed/portable/smart/simple – may operate at the same power (10W). A smart slave is treated like a master that hasn’t chosen to establish its own network and which sends WSDB requests via a proxy – though the devices themselves may be different, there is no reason to make a regulatory distinction. The DSA Model Rules collectively terms all smart devices as masters and all simple devices as clients. Simple devices use the same power limits as their master. Discounting improbable scenarios where a simple slave is mounted much higher than its master, this approach offers the greatest flexibility with no additional risk of interference.

The following table compares the various device categories:

This approach harmonises with all the different cases in both the FCC and Ofcom models, and provides a simpler and more powerful basis for TVWS regulation.